Quiet little Seattle made national news last week when a (very) longtime city councilman was defeated by an upstart and previously unknown candidate. The shocking part, though? She was a (gasp!) socialist!

Quiet little Seattle made national news last week when a (very) longtime city councilman was defeated by an upstart and previously unknown candidate. The shocking part, though? She was a (gasp!) socialist!

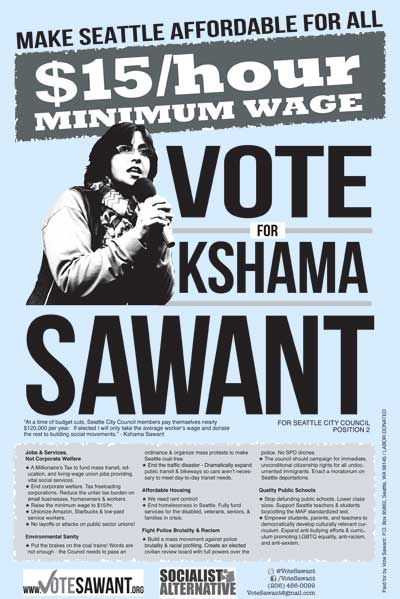

Economics professor Kshama Sawant seemed to be far behind on election night, but in the days following the election vote-counts shifted strongly her way, eventually putting her win well outside the margin that would trigger an automatic recount. By last Friday councilor Richard Conlin conceded, ending 16 years on the city council.

Media outlets on the right and left immediately overreacted to the news.

“Why is Seattle Socialist Kshama Sawant Allowed to Teach Economics?” whined a writer from Forbes after the election. Um, what??

“Seattle’s election of Kshama Sawant shows socialism can play in America,” said the Guardian. Let’s not get carried away, Guardian!

The reason Sawant won, in case any of you outside of Seattle are wondering, is that she actually ran a tight, organized and well-messaged campaign. In contrast, her opponent, a very friendly (Democratic establishment-type), non-offensive guy (I’ve chatted with him several times) never viewed her campaign as a serious threat even as she was drawing crowds to her get out the vote rallies.

I’ll stay away from drawing too many broad conclusions about the meaning behind her victory. But there is one unarguable takeaway that I think is important: At the very least, the “socialist” label wasn’t something scary that would keep people from voting for her.

And I think that’s a good thing, because the hysterical fear of “socialism” is something that’s causing Americans a great deal of unnecessary misery and struggle.

Unfortunately for our country, the education system has been gutted to such a degree that I’d bet a majority of voters couldn’t give a proper definition of socialism. Because people aren’t generally educated in various economic systems, they are easy to manipulate with overwrought smears.

But when you label everything as socialism, suddenly socialism isn’t that scary anymore. One can almost imagine a voter thinking “Well, if Obamacare is socialism, then I must be a socialist.” (For the record, it’s not. I guess technically you’d have to say the Affordable Care Act, which requires buying a product from a private corporation, is part of our Corporatocracy — corporate interests running the government. Or I guess you could argue it’s Fascism, but let’s not get into that.)

It’s important that people begin to stop being afraid of socialism because socialistic programs are the strongest protections we have ensuring we enjoy a stable, safe place to live and they are some of your most important tools for leaving work at an early age.

Doesn’t this make us a bunch of freeloaders?

Let’s dispense with the trolls right away, shall we? The classic pushback against any form of socialist endeavor is that we’ll all become weak and reliant upon the expensive nanny state government. We will no longer strive to do better and we’ll have a country of deadbeats. Worse, since we’re talking about socialism in the context of pretirement, it’s easy to imagine the complaint that the government is forking over piles of money to a bunch of lazy people.

But even people in true socialist countries have no trouble working hard to make their lives better. They don’t, however, seem to have the same fear of the financial abyss as we do in America.

And it’s silly to accuse the pretired of not paying their fair share. Most of us worked very hard for several decades. Just because we would prefer to opt-out of the final few decades of pain doesn’t mean we didn’t make our full contribution.

But socialists are weirdos

We don’t need to join the Socialist Party, stop bathing and stand on the corner handing out manifestos to recognize the value in pragmatic social support systems. We’re stronger when we join together and help each other.

The two most recognizable socialist entities in America are Medicare (“free” health care for all citizens aged 65 and up) and Social Security (basically an “insurance” program providing a small pension for older citizens). Not coincidentally, these are among the two most popular government activities every time it’s polled.

But other examples of what are technically “socialism” are all around us although often the lack of socialistic programs are often more apparent.

Obvious examples include the electricity grid you’re using to read this right now (even though our lack of investment means the American power grid is in sorry shape), the roads you drive each day (falling apart under our tires), the public education system (also starved and under assault), mass transit systems (adorably out of date), police and fire departments and, of course, our military. Those public institutions are usually well-loved, even when they frustrate us. Interestingly, though, our most hated institutions are private: our outsourced renegade army (Blackwater), private health insurance companies and Wall Street, for example.

Why are we so afraid?

So why are Americans so afraid of socialism? My opinion is that it’s the aforementioned poor education combined with an easily exploited fear of authoritarianism. Mark my words: If we ever end up with a real dictator in the U.S., it’ll happen because we were falling all over ourselves out of a fear of a hypothetical dictator.

Authoritarianism is the belief among some that they are imbued with special powers and they are therefore superior to all others and we should all submit to their crazy will. Authoritarianism actually is quite dangerous and completely possible here. Note also that authoritarians are also the first to acquiesce to power. They either need to be in charge or subservient to a strong leader. (Check out Conservatives Without Conscience for more on this. Fascinating read!)

Many of the dictatorships that live most vividly in American memories arose from left-leaning perspectives (usually locations of U.S. military intervention, see histories of Russia, Cuba, Vietnam, and North Korea, etc. for example). I think the images of those regimes become conflated with the perspective they originated from, when in fact the economic or governmental theory is irrelevant to how much your life sucks under a dictatorship. No matter what the political theory is behind these guys, it always ends up being a tiny group of insiders bossing everyone else around and stealing all the money. Concentrated power is the real enemy, not some theory on the role of government. A Communist dictator is equally as bad as a Fascist one. Big Government, Big Business, Big Religion — I hate them all equally. And when they work in collusion, I hate them all even more.

As usual, it’s about your freedom

But this isn’t meant to be another Pretired Nick political rant, fun as that may be. We’re talking about maximizing the enjoyment of your life here. We want to get out of the rat race as soon as possible and spend our time with fulfilling activities.

We reach pretirement when our passive income is higher than our living expenses. Which is why a true socialist government could complicate matters for a pretired person living off investments. From a strictly income perspective, making your pretirement numbers work is easier under a system designed to benefit the wealthy. High taxes on investment income could negatively affect many who live off their investments. Indeed, the pretired are basically structuring their lives like the super rich — on a much smaller scale. However, the cost side can be much higher without a good dose of socialism.

Either way, I don’t see much chance of investment income becoming a target for high taxes anytime soon. Our system is essentially geared from the ground up for raw capitalism. We have a long way to go in simply excising corporate cash out of the government, let alone shifting the entire system to a worker-based economy.

Hopefully people will begin to see social programs as a way to support our fellow citizens and not as equivalent to dictatorship. We have a lot of needs in this country and it’s a shame we’re ignoring so many of them. But beyond government policy, those seeking pretirement would be wise to consider how social institutions can help them reach their goals. A community that has invested in itself is a better and cheaper place to live.

Living where there is an adequate mass transit system, for example, could save you thousands of dollars each year. A community that has invested in smart development, professional police force, good lighting and has a healthy economy, is safer. You won’t need to seek out an expensive “safe neighborhood” or gated community to keep your family safe. You won’t need a ridiculous alarm system. You may not need the house with the big yard if you have great parks nearby. You can spend less on books and movies if you have a good library.

You may even wish to consider moving to another city (or country?) that has better support systems than where you are today. Seattle, for example, has great libraries, but a crappy transit system. But it is very safe. If you’re saving for college, public university in Canada costs a fraction of what it does in America — plus sweet, sweet socialized health care!

Hopefully the U.S. is maturing out of its adolescence and is ready to put away the inflammatory language whenever government spending is discussed. Strong social supports don’t limit our freedom, they expand it.

What do you think? Is it time to start being afraid of socialism and push for pragmatic changes that can make our lives better? Would you move to take advantage of a better social support system?